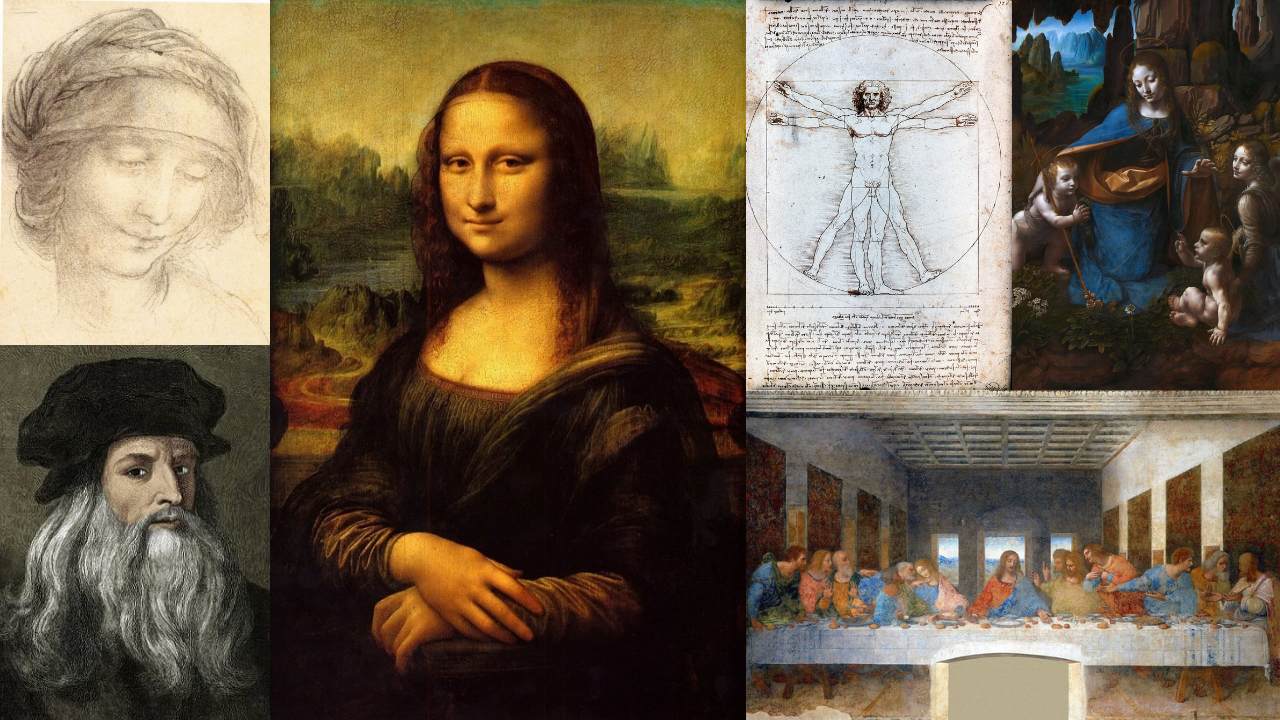

Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519) was a Renaissance Master whose scope of discoveries and achievements are unparalleled. He set an example for just how powerful certain habits can be.

With these lessons, we can superpower our ability to learn and innovate.

That’s crucial. In the 21st century, learning has become the most important skill.

And it is for this reason that we find Leonardo such an important figure to understand. How did he accomplish so much? How did he master so many arts and sciences?

Here, we continue our study into the habits that he cultivated — habits that made him one of the most remarkable individuals to ever live.

1. Pause Regularly

If you want to be a high-achieving polymath like Leonardo, it might seem like you’d have to spend every waking moment working towards something. You’ll need to be studying advanced mathematics while you let a layer of paint dry on a masterpiece, all before listening to an audiobook on your way to the patent office to claim a new invention.

But that’s not humanly possible, even for Leonardo.

Taking regular breaks is key to maintaining the energy and focus you need to do what you want to do. It also gives you perspective on what you are working on.

“It is also a good plan every now and then to go away, have a little relaxation; for when you come back to your work your judgment will be surer, since to remain constantly at work will cause you to lose the power of judgment.”

— Leonardo da Vinci

So taking breaks isn’t just about getting much-needed downtime. When we keep at a task, we can get to a point where we are chasing down detail after detail, seeing only the minutiae in front of us. Pretty soon, we forget to ask if the work as a whole is worth it, or is tending in the right direction.

In the end, when we go away for a while, we pull ourselves out of that microscopic view. We see the project as a whole. That, as Leonardo would say, is good for your judgment.

For instance, in Part 1, we talked about how powerful a notebook and regularly sketching can be. But even these are worth pausing from time to time, giving you a breather so you can return to them with renewed interest and engagement.

2. Value Diet and Exercise

Many of us feel too exhausted and time-crunched to make healthy meals and get in our exercise. These things take a lot of time, and even when we’ve decided to stick with them, they are usually the first things that get cut during a busy day, or week, or month, or year.

This is a shame, because a good diet and regular exercise are force multipliers. The effort and time you put into these two concerns will pay you back in multiples. They sharpen your mind, defend against stress, increase your expected lifespan, and keep you healthy.

New research continues to show how physical activity positively affects your central nervous system, protects you from neurological disorders, and even enhances brain functioning. Scientists have found the more physically fit you are, the better you tend to score in spatial memory tests. And if you stay active, you keep more of your gray and white brain matter into old age.

In 1515 — long before the science above was available — Leonardo wrote these wise words on the topic, most of which remain good common sense to this day:

“If you want to be healthy observe this regime.

Do not eat when you have no appetite and dine lightly,

Chew well, and whatever you take into you

Should be well-cooked and of simple ingredients.

Beware anger and avoid stuffy air.

And rest your head and keep your mind cheerful.”

— Leonardo da Vinci

It’s clear that Leonardo knew that keeping healthy was important. A well cared for body will be there for you when you need it, which you always will.

3. Apply What You Know (Or Think You Know)

Once you have a certain understanding of a topic, it isn’t enough to sigh, sit back, and feel accomplished. You have to apply what you know.

When you get to the application phase, you quickly find out just how right or wrong your ideas are. For this reason, many people are hesitant to apply their knowledge. After all, what if they fail? Then it’s back to the drawing board.

But here’s the important part of this lesson: if your ideas fail in application, you need to know that as soon as possible.

If we don’t falsify what we think, we risk holding on to unproductive and untrue beliefs. This can make it difficult to continue learning useful information. Getting these out of the way fast keeps the pipes clear for new ideas or thoughts that might prove more justifiable.

When we execute on our ideas, we don’t just falsify wrong beliefs. We also cement the best of our knowledge, and we get a more in-depth look at how our ideas work in action. That practical experience is worth much more than any amount of reading.

For Leonardo, this ability to apply his knowledge was important. When he had to flee Milan, he headed to Venice and took up work as an engineer — where his life depended on his theories being successfully applied.

And while many of his inventions never came to be (like his various flying machines), it’s the ideas that actually worked in practice that made the biggest difference in his own life.

4. Find a Mentor

Especially in the early phases of our journey, nothing can replace the power of a mentor. In many places, the world today has seen a gradual disappearance of this important relationship, but it is worth going and finding someone that can teach you what they know.

Writers like Marshall Goldsmith have discussed the importance of mentorship in a professional context, but it can extend in principle to all fields of life — from parenting to intellectual pursuits to cooking better pasta.

It goes beyond mere tutelage, because a mentor won’t only pass on practical information, they can give you an insider’s look at how a master views the problems of a particular field and synthesizes their knowledge in real-time.

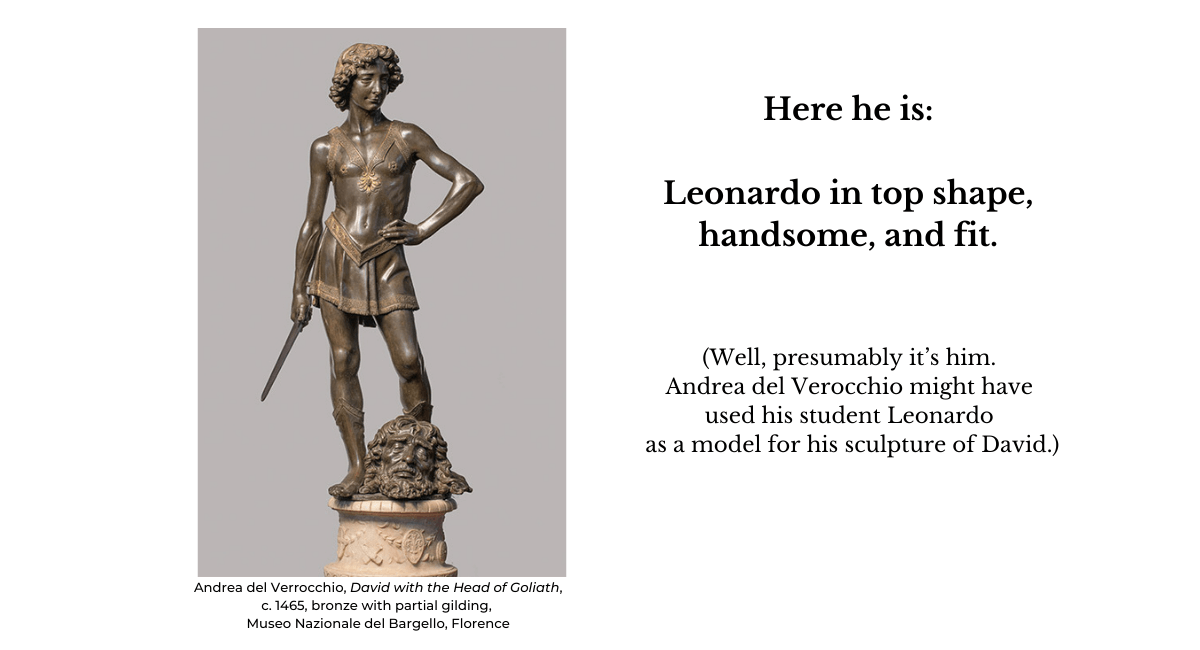

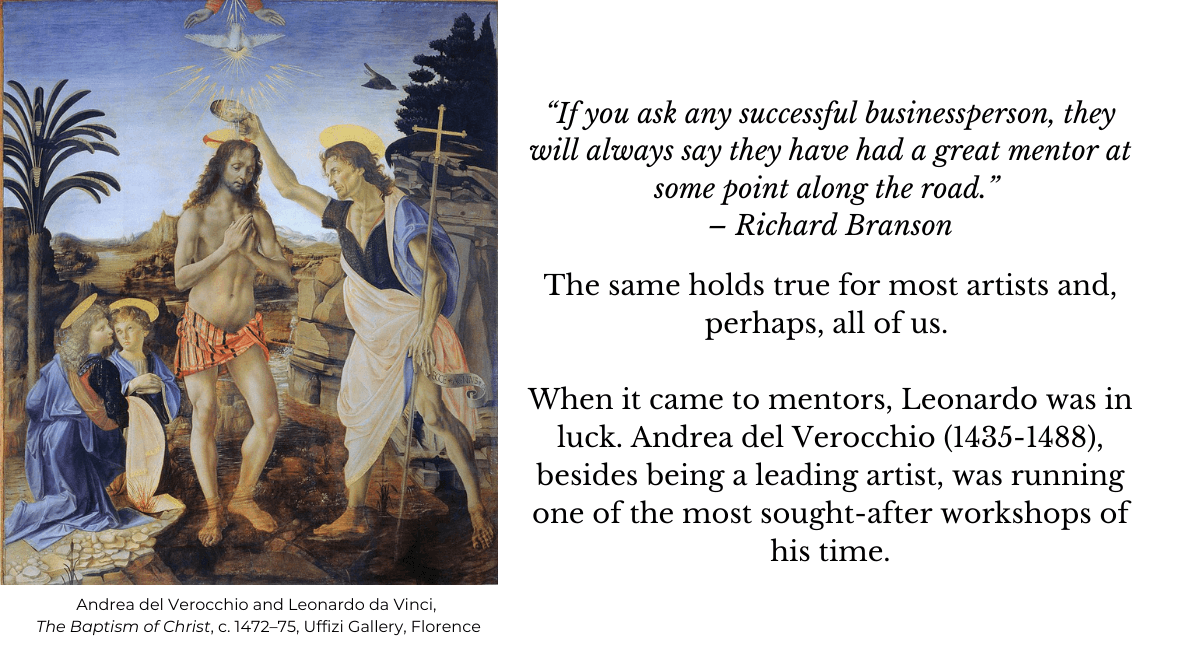

For Leonardo, Andrea del Verocchio (1435-1488) served as a mentor who provided the necessary education, guidance, and encouragement to turn a bright young man into a brilliant adult. It is interesting to see that especially in the Renaissance, a period of outstanding achievements, mentorship played a paramount role.

And when it came to mentors, Leonardo was in luck. Andrea del Verocchio, besides being a leading artist of his time, was running one of the most sought-after workshops for the rising talents. He trained the likes of Sandro Boticelli, Domenico Ghirlandhaio, and Lorenzo di Credi.

In the case of Leonardo, Andrea was perhaps too good at mentoring. It is said that when he discovered how superior the young Leonardo was at painting, Andrea put down the brush for good. Giorgio Vasari details this (possibly apocryphal) story in his famous work The Lives:

“While, as we have said, he was studying art under Andrea del Verrocchio, the latter was painting a picture of S. John baptizing Christ. Leonardo worked upon an angel who was holding the clothes, and although he was so young, he managed it so well that Leonardo’s angel was better than Andrea’s figures, which was the cause of Andrea’s never touching colors again, being angry that a boy should know more than he.”

— from Lives of the Most Eminent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects by Giorgio Vasari (1550)

The Art and Science of Learning

Like Leonardo himself, to master learning we must approach it as both an art and a science. And we must figure out how to apply all of this within our own lives.

In Part 1, we laid a foundation of habits that the Renaissance Master used to constantly improve his understanding of the world and mastery of his art. Here in Part 2, we found many ways to support these efforts, keeping us mentally and physically healthy while always ensuring we move in the right direction.

But it’s important to learn how to avoid common problems and burnout. These will allow us to link our bursts of inspiration with the more prosaic moments of steady progress. These lessons we can also take from Leonardo, and we will investigate them in Part 3 of our series.