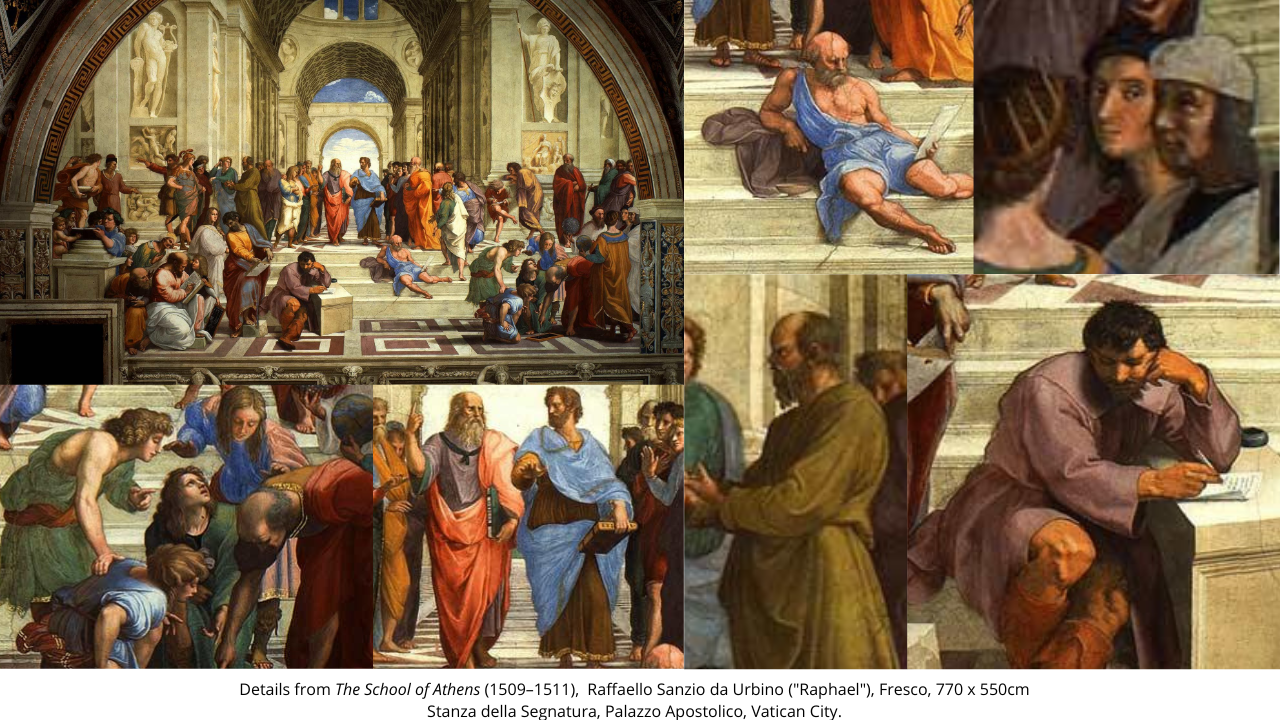

In part one, we looked at how Raphael’s The School of Athens stands as one of the best roadmaps to understanding how people learn.

While the Renaissance master painted his fresco to depict great ancient thinkers, each figure stands in for strategies of learning.

Of course, none of us only learn one single way. Our own minds are The School of Athens in miniature, with some voices a little louder than others.

But if we take the time to understand the lessons in learning that each philosopher can teach us, we can start to use our learning skills and preferences more effectively. And when we are in a position to lead, coach, and mentor others, having these preferences in mind give us the power to fit our method to the person we are teaching.

We can think of The School of Athens as a scene from our own lives. It’s a boardroom meeting, a college class, a family dinner table. Throughout our lives, we keep encountering these same broad archetypes.

Back to School

We covered the central figures in part one (Plato, Aristotle, and Socrates). Here, we finish our survey by examining all the other many characters.

In the composition, they are placed either on the side of Plato or Aristotle, and this can often give us an impression of whether concepts (Plato) or active experience (Aristotle) are core features of these thinkers. But we must remember, too, that no dichotomy is ever completely true. Everyone contains many sides.

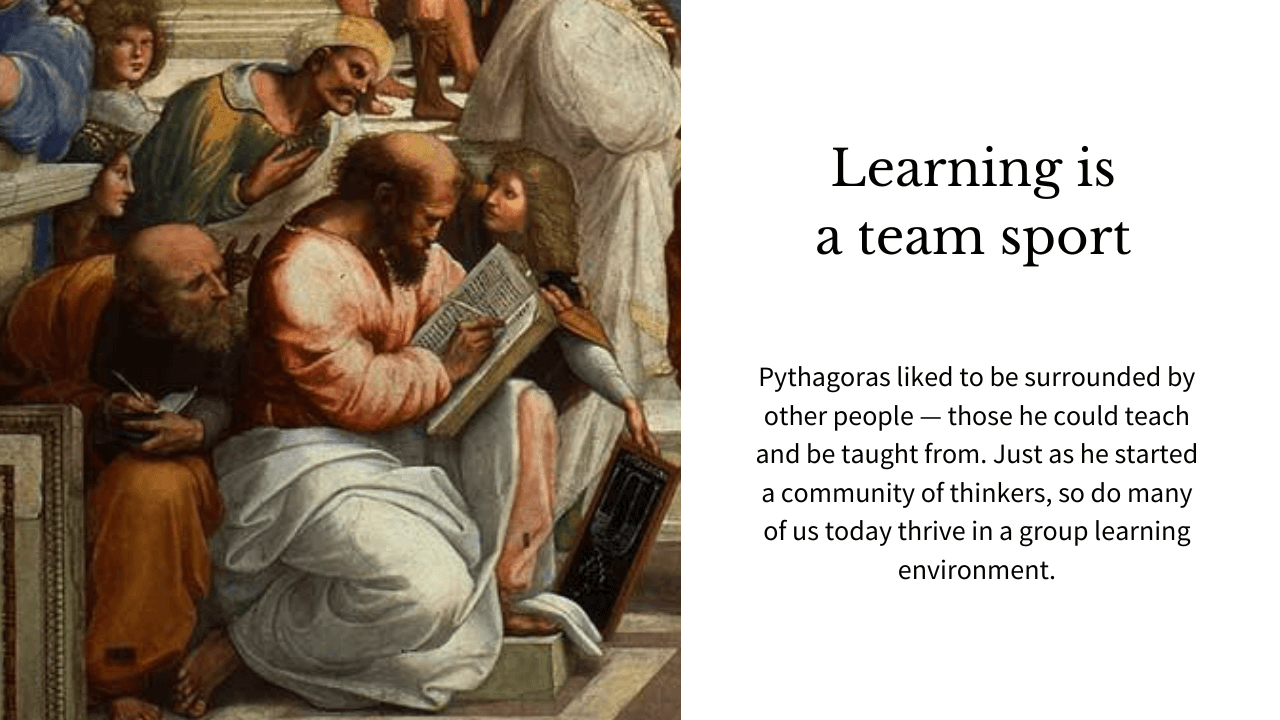

Pythagoras (570 to 495 BCE): Learn in a Group

Pythagoras was a philosopher working before the time of Socrates. He came up with many fascinating religious and political ideas.

While you might recognize the name today from the Pythagorean Theorem, this philosopher also ran a vegetarian commune built around learning and teaching great truths. He also figured out that the Earth was round, made many scientific and mathematical breakthroughs, and might have been the first person to call themselves a philosopher.

As we can see from the painting, he liked to be surrounded by other people — those he could teach and be taught from. Just as he started a community of thinkers, so do many of us today thrive in a group learning environment.

It’s as true today as it was in Raphael’s time and in Ancient Greece: learning is a team sport.

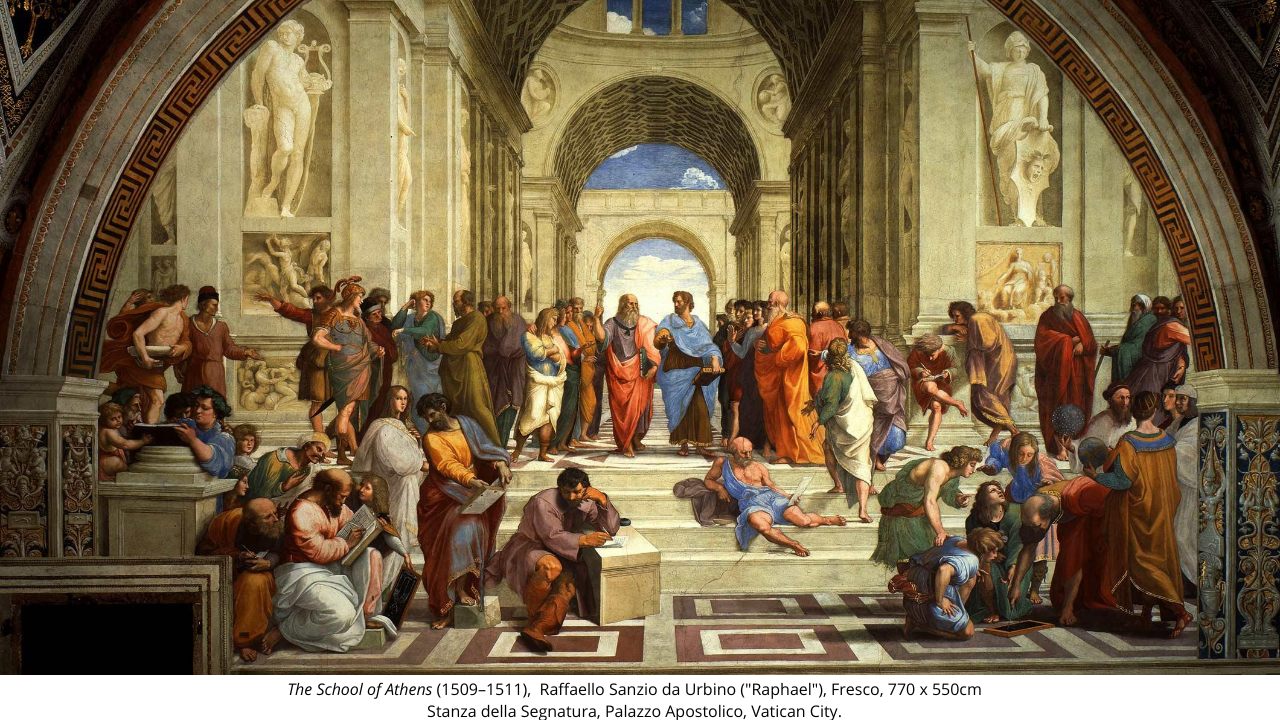

Euclid (c. 325 to 265 BCE): Learn from First Principles

Euclid is credited as more or less creating geometry as we know it. Elements, his treatise on the subject, was used as a textbook for more than two thousand years. How did he make such an enduring mark on human thought? How did his theorems hold up and provide helpful knowledge for so long?

Euclid derived all of his major breakthroughs by beginning with a few well-chosen axioms. These were bedrock ideas about how things worked. Because he limited how many he used, he could make sure he only picked the right ones. From there, he deduced and deduced and came up with a system that we still find helpful today.

In contemporary society, this is called working from first principles. It’s a very powerful way to solve problems — by peeling back all our assumptions and getting down to the essence of what we can really say we know.

And like Pythagoras, Euclid is circled by students. The one closest to him looks down in awe, maybe a bit lost. The next one looks upward, no doubt trying to integrate the insights he’s learned. The third stands up, his mastery is beginning to blossom. The final one stands back, placing a helpful hand on another pupil’s shoulder. This person has mastered the subject so well he is able to help mentor others. As for Euclid, he keeps his head down to his work, barely aware of the world around him!

When we learn, we play each of these students in order until we become Euclid himself.

Ptolemy (c 100 to 170 CE) and Zoroaster (pre-500 BCE): Learn with Stories

Ptolemy is one of the founding writers in Western astronomy, and Zoraster founded a religion in Iran that went on to influence religious thinking for millennia.

These two great astronomers of their respective times are placed together in The School of Athens (next to a possible self portrait of the artist), one holding a globe of the stars and the other a globe of the earth. What unites them both is their deep affiliations with both astronomy and astrology — looking up in the sky to find patterns that provide some kind of meaning.

While many do not believe in astrology today, we can expand on this idea to think in terms of searching for meaning. This is something we have always done. One of the most powerful ways we can continue to do this is through the art of storytelling.

Stories are the most ancient way that humans have saved and handed down wisdom and information. In our data-rich 21st century, this might seem like it’s disappeared, but that isn’t true. With so much information, we’ve never needed stories more. They help highlight what is most important and give us guides to how to act.

One of the best ways to learn is by creating a narrative arc. Where are we now? Where do we want to be? What is the problem we face? How do we overcome it? These are the questions that, when put together, tell a story.

Heraclitus (c. 500 to 400 BCE): Learn by Questioning Everything

Though very little direct evidence of his life exists, Heraclitus enjoys a vivid life in the writings of others. He thought about the unity of opposites and the human soul.

His work is, at times, inscrutable. It’s for this reason that he has always been known as “The Obscure” — quite the epithet for a writer. And yet, despite the fact that only fragments of a single work survive, he remains an important figure in the history of philosophy.

And this is for a good reason. Heraclitus questioned everything. He even appeared to make little effort to stay committed to his own ideas, fully willing to argue with his own previous conclusions. This is one of the most important ways to learn. When we question everything, we get a moment where the world is new again, and the solutions and insights that seemed impossible are now in reach.

This approach is valuable for today’s thinkers who want to come up with revolutionary new ideas — you have to be willing to find and doubt your own assumptions.

This is perhaps one of the reasons Raphael painted Heraclitus on his own. Intellectually, he had no allegiances. He stands in for all the revolutionary thinkers who had to brave those lonely first steps away from “common sense” and into the frontier of original thought.

Diogenes (c. 412 to 323 BCE): Learn Without Prejudice

Oh Diogenes, one of the most entertaining philosophers who ever lived! Tales of his exploits are the stuff of legend. In one (possibly apocryphal) story, he owned only a bowl because that’s all he needed. When he saw a child drink water using his hands as a cup, Diogenes threw away his bowl.

He was a social critic, always quick to confront the hypocrisy and poor virtues of Athenian good manners — he even made fun of Alexander the Great to his face. He lived in poverty, according to the virtues that he argued for.

While many at the time were scandalized by his actions, he remains so well known today because of his commitment to his ideals. And we are able to learn from him only if we are willing to set aside our prejudices and listen. You never know who your next teacher will be, or what lesson it is you need to hear.

Young Student With Notepad: Grab a Pen

This unnamed and unknown student leans against the wall and props up his notepad on a leg. It seems a small detail, something you might skip over, but this image gives us a great idea for learning: grab a pen!

Imagine standing in this beautiful school filled with the great thinkers of ancient Greece. How could you capture all the interesting wisdom and theories floating through the air? With a pen of course. This student knows that only when you begin writing things down and capturing thoughts as they come that you can really learn all the information you are encountering.

Learning Happens Everywhere

This next lesson zooms out to look at the setting of the painting. It’s easy to miss, but do you notice how specific and realistic it seems? It might come as a surprise then that it is completely made up.

Let’s learn a lesson from this as well: that there is no one special place where learning happens. It doesn’t begin and end in a classroom, or a training session. Instead, it continues to happen throughout our lives.

As a leader, you need to understand that people will continue to learn lessons wherever they are. Supporting that process means understanding the many ways and places they will learn.

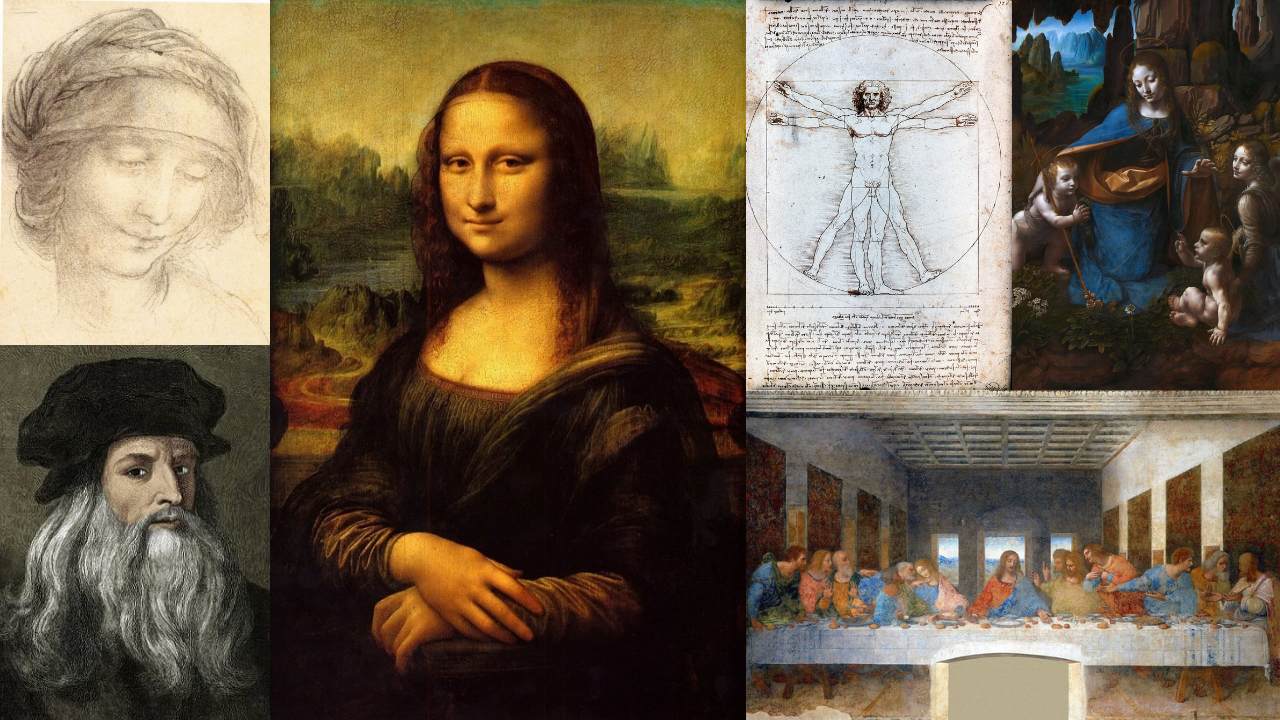

Raphael (1483 to 1520): Use What You Learn

As mentioned above, Raphael (whose birth name was Raffaelo Sanzio da Urbino) likely placed himself in the painting over by the astrologers. This was a bold move. The artist had yet to make a name for himself, and while this would prove to be the masterpiece that rocketed him to master status, no one knew that yet.

But despite his relative youth, here he was, painting at the Vatican. Not only that, he was tasked with creating an enormous fresco that would make a statement about the history of Western thought and the eternal faculties of the human mind. He’d trained, practiced, and worked up to this point. He knew he was chosen for a reason. And when he was given the opportunity, he took it.

One of the most important parts of learning new skills is to actually use them. Or, as Harvard Business School professor Ananth Raman keeps reminding his students: “When your time comes, take the shot.”

Raphael’s example sums up every other lesson the painting gives us. The final piece to learning is always the point where you go out into the world and act.

If you are ready to begin developing talent in your own organization, contact Autoris today. Where we go, people succeed.