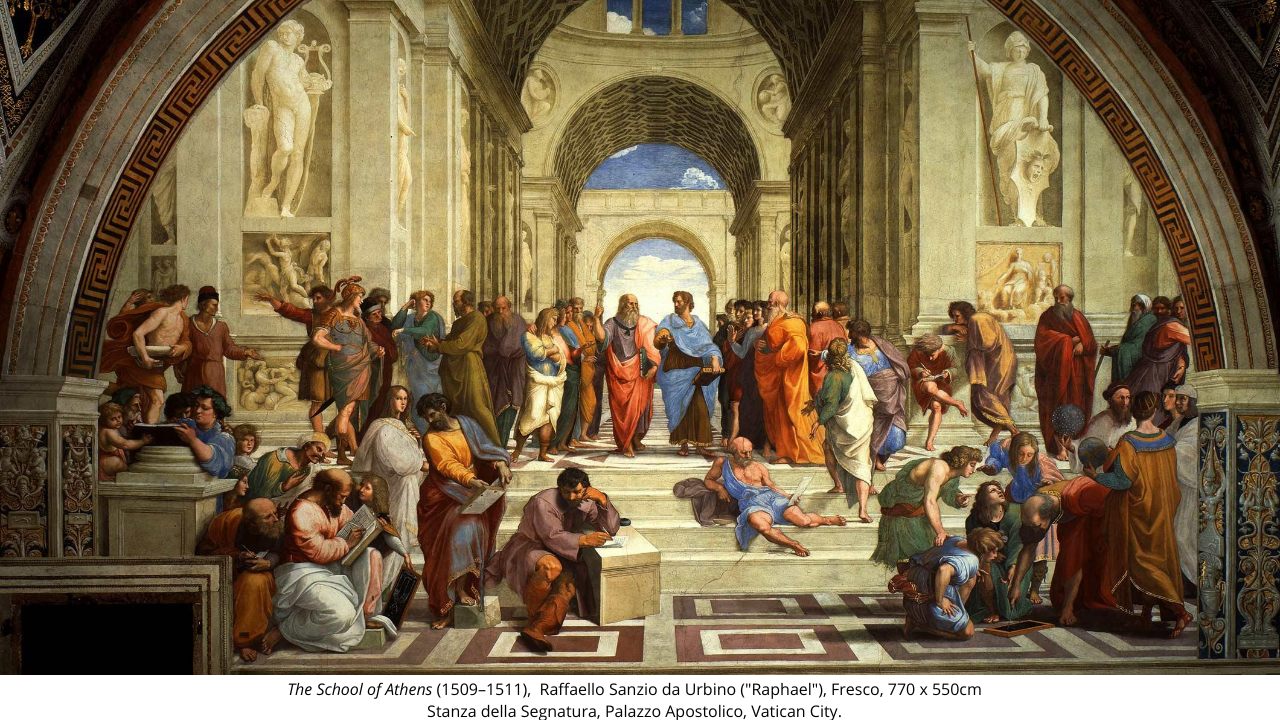

The School of Athens is an undisputed masterpiece by Italian High Renaissance artist Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino (1483-1520), better known as Raphael. It stands as an imposing fresco in the Stanza della Segnatura in the Papal Palace in Rome, its size matching the enormous scope of the work.

In the painting, great ancient thinkers are arranged in a grand tableau, standing in an architectural wonder that is rendered in a striking one-point perspective. The lush detail and compelling composition secured the young Raphael’s place in the highest echelons of the Renaissance Masters, and the fresco remains a landmark achievement in art history.

Gathered beneath the midday sun under the statues of Apollo and Athena, the philosophers are all caught in a moment that evokes their beliefs, as well as their approach to thinking and their relationship (whether cordial or fraught) to one another. It is an entire course on Hellenistic thought in a single painting.

As entrepreneurs, team leaders, coaches, professionals and human beings living in the 21st century, we might be skeptical that this painting can be relevant to us. But though Raphael completed the work in the early 16th century, and though it brings us a scene from two millennia before our time, taking in The School of Athens today gives us striking examples of how we might think and how we might ask our own questions of the world.

Why the School of Athens Matters

If we look carefully, we see that The School of Athens provides us with a rich catalog of the many ways we learn about the world .

For us, this isn’t only a painting of an ancient scene. It is the painting of the modern workplace, the modern community center, the modern home.

In an age of information and technological flux, upskilling and reskilling is a constant struggle. Learning how to learn and how to teach others have become the true coins of the realm.

The importance of learning has not protected it from confusion, unfortunately. Many educators are still trying to use outdated and disproven ideas, like the idea that human learning comes down to the four simple styles (visual, auditory, reading and writing, and kinesthetic). What’s worse, reliance on internet access has convinced many that the easy online search can replace mastery of a subject, at least in a pinch.

But learning is much more individual than a simplistic four-mode model can describe. And learning is about much more than accumulating knowledge.

This is critical. For an individual, optimal learning is a mixture of many preferences. And learning itself is not an event — it’s a process of gaining and changing knowledge, skills, habits, behaviors, or attitudes.

Did the young Raphael know all this when he traveled to the Vatican to begin sketching The School of Athens? Maybe, maybe not. It doesn’t matter. His masterpiece nevertheless provides us with a roadmap to these insights. And it solidifies these abstract concepts into archetypal characters that we can meet and cultivate in ourselves and in others.

That is art’s power to teach us about learning.

Too often, we assume most people like to learn the way we do. But that’s wrong. One look at the crowded scene in Raphael’s painting can tell us that.

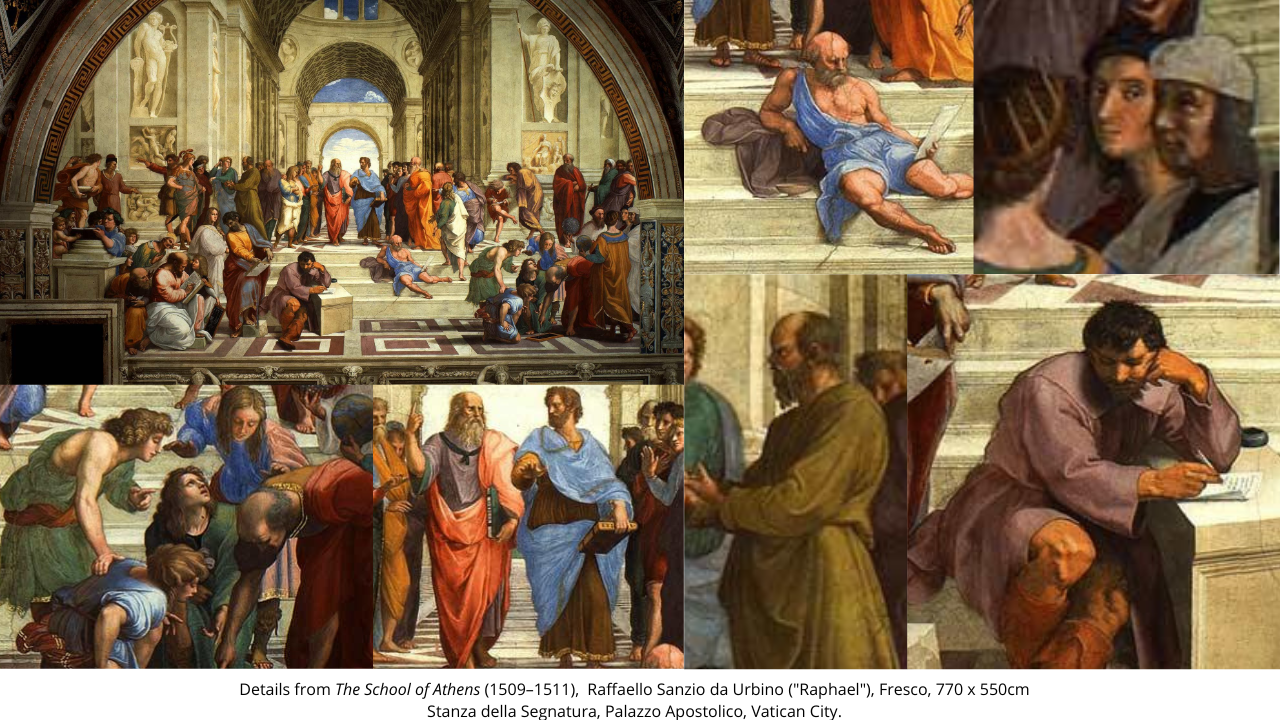

When we examine the fresco in detail, we can begin to unearth the profound wisdom lying inside. And we can return to our lives ready to learn, teach and grow. And in part one of this series, we’ll start by looking at the three central characters.

The Philosophers in the Center of the World

In the center of the composition stand the two major figures of Ancient Greek philosophy: Plato and Aristotle. To the side stands Socrates, the one who started the tradition both these thinkers come from.

Plato points up to the world of forms — the essential patterns that he believed all reality stems from. Aristotle reaches out to the world of the viewer — as he preferred to observe reality before drawing his conclusions.

While they have different approaches, they do not have conflict. Plato mentored Aristotle, and humanity has learned so much from both approaches. But their difference is placed in the center of the painting because it represents the core split in learning preferences.

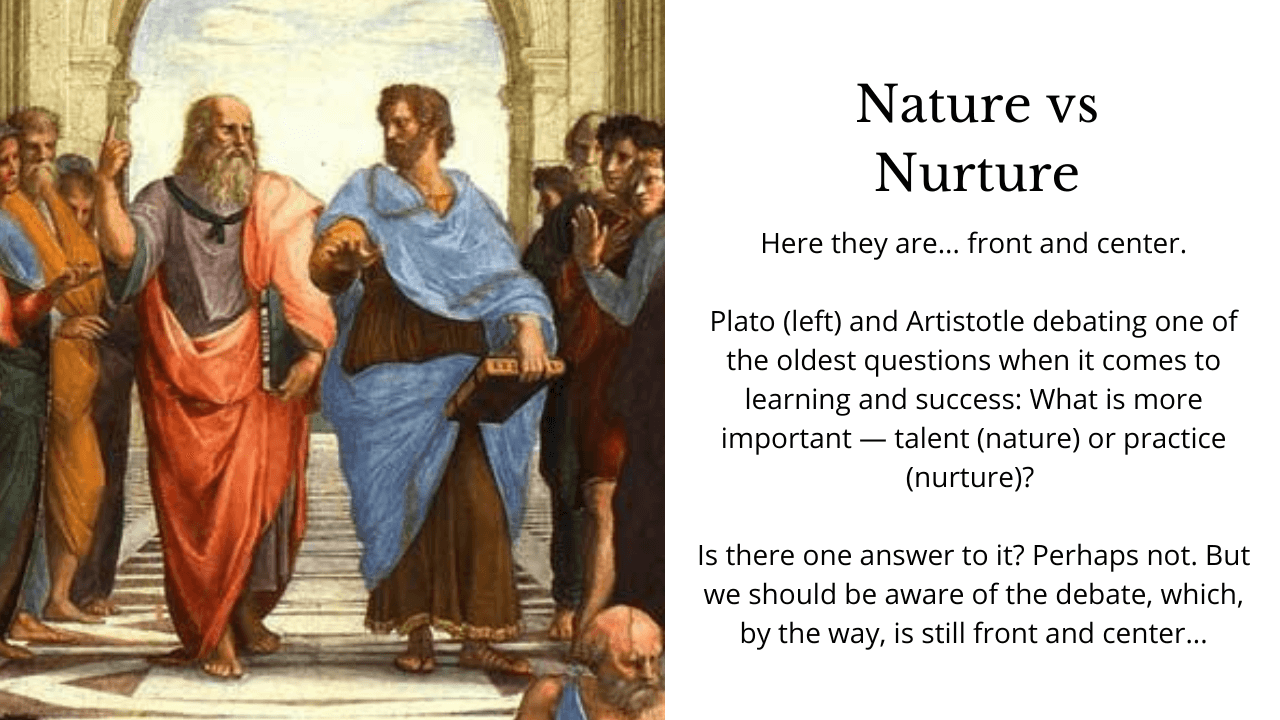

There is also a link here to the divide between nature and nurture. We are born with certain aptitudes and traits that form us. This element of nature, or Plato’s world of forms, is essential to our individual abilities. But we cannot rule out the experiences we have, both positive and negative, that shape us just as profoundly. This element of nurture, or Aristotle’s materialism, shows us the importance of what happens in the world.

It should be mentioned that no person will be entirely like Plato or Aristotle. But they will no doubt recognize the divide is there in all of us. And in the 21st century, we can draw profound lessons from these central figures and the dichotomy they represent.

Plato (c. 427 to 347 BCE): Learn from Concepts

Plato was a prolific writer in ancient Greece. His works include The Republic, where he laid down the foundations of political philosophy. Instead of writing treatises, he preferred writing theatrical dialogues between Socrates and other people. He is best known for his analogy of the cave that teaches us about the world of forms.

The world of forms is abstract, and many learners are most at home here. They gather information by reading or listening, taking notes and drawing their own conclusions. They can look to spreadsheets of data and see patterns. They can make use of concepts, applying them to the situation at hand.

This conceptual approach is great for coming up with new ways of doing things and sorting the information coming in. Without it, there isn’t much we can do with data or resources. In that way, these learners can often be visionaries.

Aristotle (384 to 322 BCE): Learn from Hands-On Experience

Aristotle was a student of Plato. He went on to write a range of works that helped establish the basis of logic, ethics and science. He was also a talented mentor, taking none other than a young Alexander the Great under his wing.

Learning by experience indicates the other major half of human learning. Getting practical, hands-on training is crucial for everyone, but some more than others. These are the people who prefer to begin the board game immediately, rather than read through the rules.

This approach also saves us from the overreach of more abstract and conceptual thinkers. There are times when leaders are so convinced by an idea that they ignore the evidence coming in — mistaking alarm bells for windchimes. But the experience-based approach creates people that can adapt easily.

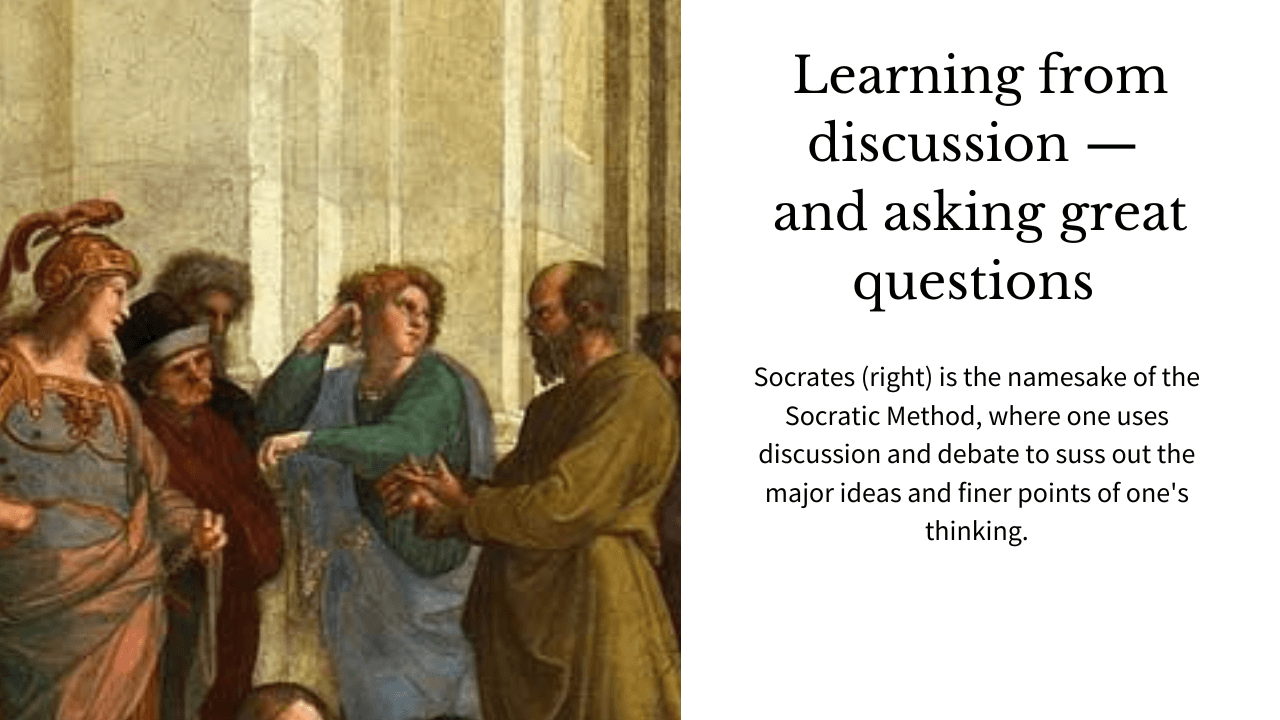

Socrates (c. 470 to 399 BCE): Learn from Discussion

While Socrates never wrote anything (we know what he thought thanks to his pupil Plato), he said a lot. He is the namesake of the Socratic Method, where one uses discussion and debate to suss out the major ideas and finer points of one’s thinking.

Many people learn through discussion — it helps them clarify what they think and discover new points of view they never thought of before. While it can lead to being a bad dinner party guest when taken to the extreme, the ability to discuss ideas is especially helpful when working in groups.

In fact, friendly debate and deep discussion are the best ways that peers can teach each other. While mentors are important, peers in learning give you people to test your new ideas and skills with. Not to mention, they give you that little competitive spark.

You might also notice that in his dialogues, Socrates asks far more questions than he gives answers. That’s because learning is much more about asking than telling. As Albert Einstein once said, “If I had an hour to solve a problem and my life depended on the solution, I would spend the first 55 minutes determining the proper question to ask. For once I know the proper question, I can solve the problem in less than five minutes.”

A World of Learning Preferences to Explore

In part two, we’ll examine the other philosophers who make up the scene. Raphael’s The School of Athens has many more insights to share with us about all the learning preferences humans have.

But the three we’ve covered so far give us a great start. They show us the major themes that the other thinkers will take up, reconfigure, and make their own.

If you would like to discover more ways to develop success in your own organization, watch out for part two of this series or reach out to Autoris today .